How much does the lay of the land influence the outcome of a fight? When we think of anime battles, we generally tend to focus on the combatants themselves — their specific abilities and how their various powers might play off each other. But battles are more than a contest of pure abilities, and in conflicts with a grand scale, the geography of the landscape and positioning of forces can be even more consequential than individual strength. I always enjoy a story that manages to evoke a sense of geographical solidity, moving beyond the simple “combatants in an open field” to embrace fights that ramble across castles, mountains, or even entire kingdoms. Recently, I’ve been delighted to see how well Eiichiro Oda evokes a sense of space in his monumental One Piece.

Like many of One Piece’s best elements, Oda’s skill for manipulating geography as a dramatic tool develops steadily over time. But even in the saga’s early arcs, it’s easy to see how he’s already using time and space to add unique dynamics to his fights, beyond the simple “can this character beat that other character.” Usopp’s introductory arc offers the earliest examples of this tendency, hinging its conflicts on drama like “can we intercept the enemies as they’re making landfall,” and making Kuro’s movement across the island a consistent, evolving threat. These flourishes might not seem that substantial, but they give the conflict a sense of dynamics beyond pure collisions of force, while simultaneously giving Syrup Village a greater sense of lived-in solidity, making it that much easier to care about the village’s fate.

Later on, things start getting far more geographically interesting. As the Straw Hats arrive at unique islands like Little Garden and Whiskey Peak, the pure excitement of discovering strange new ecosystems and natural wonders starts to become one of the show’s greatest appeals. While any number of shows offer exciting battles, One Piece’s emphasis on the joy of discovery, rather than combat, consistently sets it apart. Through his unique environments, Oda makes each new island a reward unto itself, simply as a place to be discovered and explored.

At the same time, Oda begins integrating these strange, unique environments into the fundamental course of his narrative drama. Along with the pirate Wapol, one of the principal antagonists of the Drum Island arc is simply the inhospitable mountain range the arc inhabits. The Straw Hats contend with sheer cliff faces, avalanches, frigid temperatures, and much else, taking advantage of the scenery to sculpt conflicts that circumvent the genre’s tendency toward purely fight-based drama. As a result, the audience is not only offered a more diverse array of hooks but also gets a much clearer impression of Drum Island as a living place, not just a name and a villain.

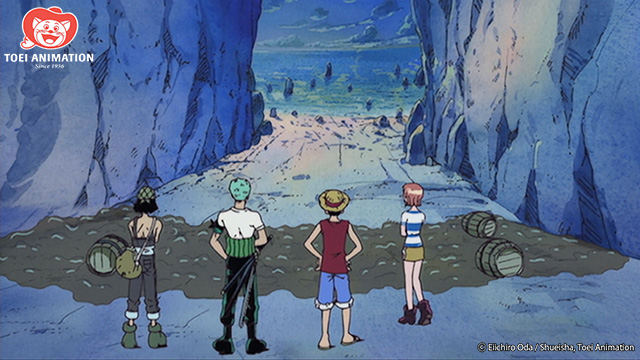

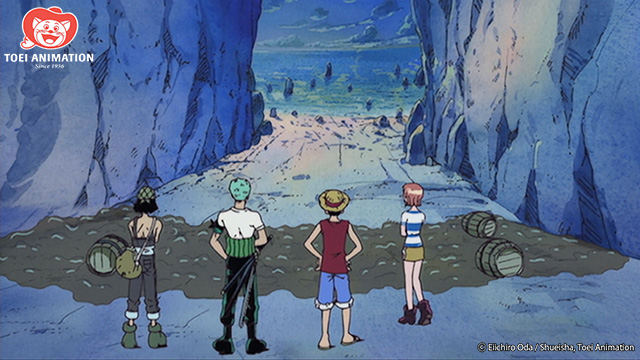

By the time the Straw Hats reach Alabasta, Oda’s geographic ambitions have grown even grander, as he begins to introduce full-on maps of the overall field of conflict. Alabasta’s conflict stretches across an entire country and offers the audience the perspective of a general in his field tent, marshaling forces for total war. Conflicts can now be constructed purely around timing and geography, like when Luffy squares off with Crocodile in order to let his crew cross the desert, or the team’s desperate gambit to get Vivi inside the capital city. Cities now have a sense of substance and specificity; each new venue is distinct, with even the various desert towns possessing more individuality than the East Blue’s largely similar islands.

Because of this, as Alabasta’s cities fall, their ruin feels appropriately apocalyptic — like something of true value is being lost. Alabasta’s cities have histories and personalities, and watching them be destroyed makes both the scale of these conflicts and the brutality of their villains painfully clear. When stakes and geography are unclear, fights can start to feel indulgent or weightless. By grounding Alabasta’s battles in the desperate will of its people and the distinct beauty of their homes, Oda makes every clash feel like the last bulwark against the end of the world.

By the time One Piece arrives at Skypiea, all of these emerging strengths have clicked into place, making for an arc that first dazzles through the pure inventiveness of its scenery and later thrills through the tactical complexity of mastering that terrain. The journey through Skypiea allows all of the Straw Hats to express their distinct strengths, make friends across a variety of cultures, and discover hidden histories as they navigate cloud rivers, ancient forests, and mysterious ruins. With Skypiea’s history and geography so clearly established, the arc is able to culminate in battles with a truly absurd sense of scale, where it feels like the sky itself is falling.

Since then, One Piece has maintained this marvelous fusion of adventurous scene-setting and destructive finales, with arcs like Enies’ Lobby demonstrating its profound dramatical appeal. It’s one thing to be told that some character’s power is frightening; it’s quite another to see how their power impacts the very geography of the world around them, shattering bridges and toppling towers as they go. Through Enies’ Lobby and Thriller Bark, Oda demonstrates that establishing a clear hostile environment is just as effective as a friendly one — after all, who doesn’t want to see a monument to evil get reduced to rubble, one strike at a time? One Piece’s emphasis on geography bolsters both its creative and dramatic appeal, and I can’t wait to see how Oda employs this trick next!

Nick Creamer has been writing about cartoons for too many years now and is always ready to cry about Madoka. You can find more of his work at his blog Wrong Every Time, or follow him on Twitter.

Do you love writing? Do you love anime? If you have an idea for a features story, pitch it to Crunchyroll Features!

from Latest in Anime News by Crunchyroll! https://ift.tt/3bxg8Vq

How much does the lay of the land influence the outcome of a fight? When we think of anime battles, we generally tend to focus on the combatants themselves — their specific abilities and how their various powers might play off each other. But battles are more than a contest of pure abilities, and in conflicts with a grand scale, the geography of the landscape and positioning of forces can be even more consequential than individual strength. I always enjoy a story that manages to evoke a sense of geographical solidity, moving beyond the simple “combatants in an open field” to embrace fights that ramble across castles, mountains, or even entire kingdoms. Recently, I’ve been delighted to see how well Eiichiro Oda evokes a sense of space in his monumental One Piece.

Like many of One Piece’s best elements, Oda’s skill for manipulating geography as a dramatic tool develops steadily over time. But even in the saga’s early arcs, it’s easy to see how he’s already using time and space to add unique dynamics to his fights, beyond the simple “can this character beat that other character.” Usopp’s introductory arc offers the earliest examples of this tendency, hinging its conflicts on drama like “can we intercept the enemies as they’re making landfall,” and making Kuro’s movement across the island a consistent, evolving threat. These flourishes might not seem that substantial, but they give the conflict a sense of dynamics beyond pure collisions of force, while simultaneously giving Syrup Village a greater sense of lived-in solidity, making it that much easier to care about the village’s fate.

Later on, things start getting far more geographically interesting. As the Straw Hats arrive at unique islands like Little Garden and Whiskey Peak, the pure excitement of discovering strange new ecosystems and natural wonders starts to become one of the show’s greatest appeals. While any number of shows offer exciting battles, One Piece’s emphasis on the joy of discovery, rather than combat, consistently sets it apart. Through his unique environments, Oda makes each new island a reward unto itself, simply as a place to be discovered and explored.

At the same time, Oda begins integrating these strange, unique environments into the fundamental course of his narrative drama. Along with the pirate Wapol, one of the principal antagonists of the Drum Island arc is simply the inhospitable mountain range the arc inhabits. The Straw Hats contend with sheer cliff faces, avalanches, frigid temperatures, and much else, taking advantage of the scenery to sculpt conflicts that circumvent the genre’s tendency toward purely fight-based drama. As a result, the audience is not only offered a more diverse array of hooks but also gets a much clearer impression of Drum Island as a living place, not just a name and a villain.

By the time the Straw Hats reach Alabasta, Oda’s geographic ambitions have grown even grander, as he begins to introduce full-on maps of the overall field of conflict. Alabasta’s conflict stretches across an entire country and offers the audience the perspective of a general in his field tent, marshaling forces for total war. Conflicts can now be constructed purely around timing and geography, like when Luffy squares off with Crocodile in order to let his crew cross the desert, or the team’s desperate gambit to get Vivi inside the capital city. Cities now have a sense of substance and specificity; each new venue is distinct, with even the various desert towns possessing more individuality than the East Blue’s largely similar islands.

Because of this, as Alabasta’s cities fall, their ruin feels appropriately apocalyptic — like something of true value is being lost. Alabasta’s cities have histories and personalities, and watching them be destroyed makes both the scale of these conflicts and the brutality of their villains painfully clear. When stakes and geography are unclear, fights can start to feel indulgent or weightless. By grounding Alabasta’s battles in the desperate will of its people and the distinct beauty of their homes, Oda makes every clash feel like the last bulwark against the end of the world.

By the time One Piece arrives at Skypiea, all of these emerging strengths have clicked into place, making for an arc that first dazzles through the pure inventiveness of its scenery and later thrills through the tactical complexity of mastering that terrain. The journey through Skypiea allows all of the Straw Hats to express their distinct strengths, make friends across a variety of cultures, and discover hidden histories as they navigate cloud rivers, ancient forests, and mysterious ruins. With Skypiea’s history and geography so clearly established, the arc is able to culminate in battles with a truly absurd sense of scale, where it feels like the sky itself is falling.

Since then, One Piece has maintained this marvelous fusion of adventurous scene-setting and destructive finales, with arcs like Enies’ Lobby demonstrating its profound dramatical appeal. It’s one thing to be told that some character’s power is frightening; it’s quite another to see how their power impacts the very geography of the world around them, shattering bridges and toppling towers as they go. Through Enies’ Lobby and Thriller Bark, Oda demonstrates that establishing a clear hostile environment is just as effective as a friendly one — after all, who doesn’t want to see a monument to evil get reduced to rubble, one strike at a time? One Piece’s emphasis on geography bolsters both its creative and dramatic appeal, and I can’t wait to see how Oda employs this trick next!

Nick Creamer has been writing about cartoons for too many years now and is always ready to cry about Madoka. You can find more of his work at his blog Wrong Every Time, or follow him on Twitter.

Do you love writing? Do you love anime? If you have an idea for a features story, pitch it to Crunchyroll Features!

That's the article: FEATURE: How Geography Affects Battle in One Piece

You are now reading the article FEATURE: How Geography Affects Battle in One Piece with link address https://tenseishitaraslimedattakennews.blogspot.com/2021/05/feature-how-geography-affects-battle-in.html

Post a Comment